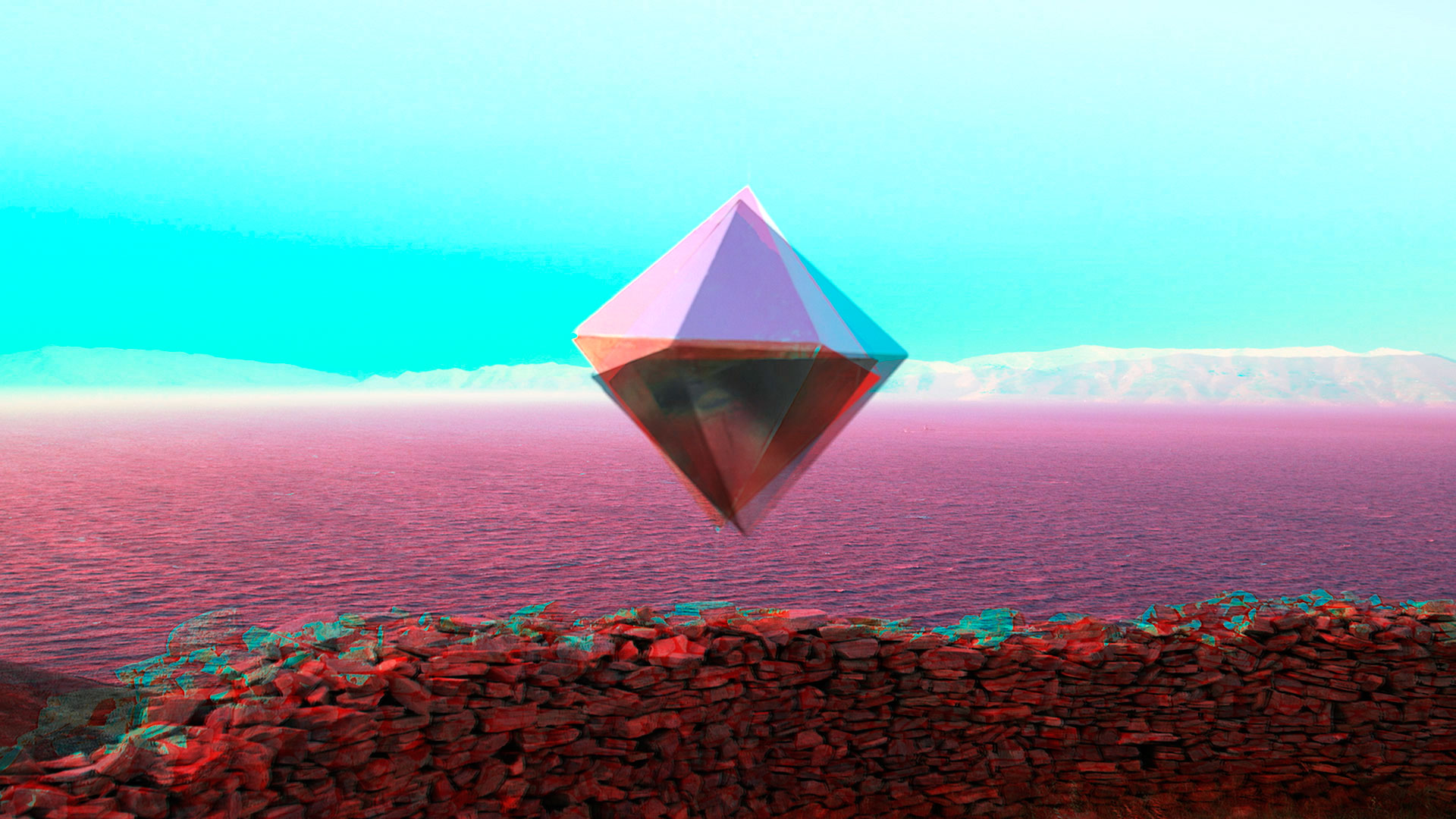

Still from Last Things (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

1ON1 with Deborah Stratman

Nicky Ni | March 27, 2023

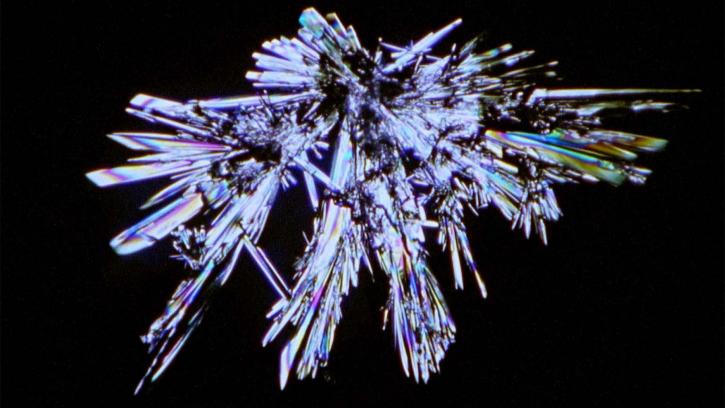

The 33rd Onion City Experimental Film Festival is just around the corner! Taking place between March 30 and April 9, the Festival this year will open with the Chicago premiere of filmmaker Deborah Stratman’s new film, Last Things (2023), a mesmerizing, speculative and eye-opening experimental documentary centering the most fundamental materials on earth, rocks.

Deborah herself also needs little introduction. An award-winning filmmaker who welcomes national and international accolades, she has been prolifically producing research-based works that encompass film, video, installation, curation and writing, investigating complexities such as power, control, surveillance, belief, and how these altogether are intertwined in human societies. Deborah is currently living in Chicago and teaching at University of Illinois. And most importantly, she is one of the most intelligent, amiable, energetic and passionate people I’ve ever met.

Leading up to the screening on Thursday, March 30, I am very honored to have the opportunity to pose a handful of questions to Deborah. A lot of very insightful interviews and conversations already exist out there. I recommend “Viva La Gap” with D. Taylor on Expressionless and an interview with Julie Perini on Incite. To fill in some gaps, so to speak, this interview focuses on elements of her films that are perhaps less discussed, and shines light upon her non-film and public works, including curatorial and site-specific installations. Every mention is hyperlinked to the project page so you know where you can get more info.

I also highly recommend that you read Deborah’s writings, for example, “Keeler is where the postbox is” published on The Hoosac Institute, and “The Willamette meteorite,” on This Long Century. They are poetic, whimsical and refractive, taking you by the hand to travel across time and history. Everything at once.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Deborah herself also needs little introduction. An award-winning filmmaker who welcomes national and international accolades, she has been prolifically producing research-based works that encompass film, video, installation, curation and writing, investigating complexities such as power, control, surveillance, belief, and how these altogether are intertwined in human societies. Deborah is currently living in Chicago and teaching at University of Illinois. And most importantly, she is one of the most intelligent, amiable, energetic and passionate people I’ve ever met.

Leading up to the screening on Thursday, March 30, I am very honored to have the opportunity to pose a handful of questions to Deborah. A lot of very insightful interviews and conversations already exist out there. I recommend “Viva La Gap” with D. Taylor on Expressionless and an interview with Julie Perini on Incite. To fill in some gaps, so to speak, this interview focuses on elements of her films that are perhaps less discussed, and shines light upon her non-film and public works, including curatorial and site-specific installations. Every mention is hyperlinked to the project page so you know where you can get more info.

I also highly recommend that you read Deborah’s writings, for example, “Keeler is where the postbox is” published on The Hoosac Institute, and “The Willamette meteorite,” on This Long Century. They are poetic, whimsical and refractive, taking you by the hand to travel across time and history. Everything at once.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

***

Nicky Ni:

Sound is certainly an important element

in your work, exemplified by the Chicago Works installation at the Museum of

Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), Feeling Tone (2020) and the film Hacked Circuit (2014).

There are so many incredible interviews in which you talked about the usage of

sound as space making in your moving image works. As a background question:

when and how did you become fascinated by sound? What was the process of

training yourself to be the sound editor of your films?

Deborah Stratman:

I’ve been sound-sympathetic as long as I can remember. I sang and

played various instruments, though none very well; my father played music; my middle

brother Steve can play virtually any instrument he picks up. It’s mind-boggling

and mildly annoying. There was always music in the house, live music but also records,

cassettes, radio. I was generally interested in acoustics and transmission,

though I didn’t call it by those names. As a kid I would lay on the window

ledge which was hollow and listen to the way the wooden cavity amplified my

digestive track. In my 20s, I started learning about synthesizers and the

history of field recording and musique concrète. My investment in vibration is

a sort of base note to my life.

When I first started editing, it was on celluloid and reel-to-reel ¼” tape making sound collages. I was transferring audio to magnetic materials and cutting that. So, I arrived at editing through the tactile. Later I learned digital video editing systems, most recently Premiere and DaVinci. Pro Tools is my go-to sound software for fine tuning and mixing. You learn sound editing by doing it, over and again. It helps to have a sense of rhythm, but that can be developed and finessed. Start to learn what sort of spaces you want to create. The essential bit is learning how to listen. Be a radical listener.

When I first started editing, it was on celluloid and reel-to-reel ¼” tape making sound collages. I was transferring audio to magnetic materials and cutting that. So, I arrived at editing through the tactile. Later I learned digital video editing systems, most recently Premiere and DaVinci. Pro Tools is my go-to sound software for fine tuning and mixing. You learn sound editing by doing it, over and again. It helps to have a sense of rhythm, but that can be developed and finessed. Start to learn what sort of spaces you want to create. The essential bit is learning how to listen. Be a radical listener.

Excerpt of Hacked Circuit (2014). Video courtesy of the artist.

NN:

When

is sound the starting point for beginning a project?

DS:

On occasion, sound will be the germination of a film. For example,

I’ll hear a clip from an interview and realize I can use that as catalyst for

the rest of the film, as with the opening conversation of Optimism (2018).

Or if the piece is a music video, as with Laika (2021)

for Olivia Block. For a film liked Hacked Circuit, sound was conceptually

central, focusing on foley artistry and sonic surveillance. But it’s more

common that sonic ideas offer themselves up later, during the editing. With my

non-film projects, sound is often a catalyst. As with the public speeches that

populated PA System (2012),

or Studs Terkel’s reconstructed radio booth for Feeling Tone, or the Ball

& Horn (2011 - ongoing) sculptures.

NN:

In Laika, Xenoi (2016) and also Last

Things (2023),

there are scenes where a reflective surface, such as a mirror or a prismatic

object, appears at the center of the images, gently reflecting the blue sky or

overexposed by white light. Similar motifs return to your public art Ball

and Horns and Augural Pair (2011). Whenever I see this, I think of

“Aleph” by Borges, for some reason. They seem to belong to a realm beyond the

film itself, an outer-worldly thing, a portal of some sort that can teleport

you to a different time and space.

Still from Xenoi (2016). Image courtesy of the artist and Lightwork.

DS:

Portals are inviting. A mirror in the cinema is a way to suggest a

universe parallel to the one already represented. It can suggest an Other. A

visitor. A guest. I like that mirrors in the landscape can flip so easily

between being a hole, an eye, a reflection, a star.

They’re not mirrored, but this same idea shows up in Vever (for Barbara) (2019). The Vever drawings that appear as superimposed illustrations, and then later as punched out shadows of themselves, are doors not only for the Loa* to pass, but also for the speech and gestures of Maya Deren, Barbara Hammer, indigenous lady weaver-historians, the girls of the market and myself. There’s also a nod to the ultimate human portal at the end of the film, thanks to some enterprising self-portraiture by Hammer.

* Haitian Vodoun gods

They’re not mirrored, but this same idea shows up in Vever (for Barbara) (2019). The Vever drawings that appear as superimposed illustrations, and then later as punched out shadows of themselves, are doors not only for the Loa* to pass, but also for the speech and gestures of Maya Deren, Barbara Hammer, indigenous lady weaver-historians, the girls of the market and myself. There’s also a nod to the ultimate human portal at the end of the film, thanks to some enterprising self-portraiture by Hammer.

* Haitian Vodoun gods

NN:

In another interview with Julie Perini,

you mentioned that you started to make public work in the early 2000s as a

reaction to the limitations that you felt from the experimental film world.

That materializing participatory work expands your audience and provides

different access. Your moving image works always have the power to conjure a

spatial experience: dots are connected across time, scales, realities, through

images and sound. In reverse, when you approach public art and installation, do

you also think filmically? I’m thinking about your installation at MCA, which

can be read as a film set; your curatorial work TEX HEX: Past Forward Pop-Up Floating Cinema (2011),

where people watched moving image work and tuned in via the radio for sound; I

was also looking at your early works such as Ahbeyezyana (2005)

and FEAR (2004-14).

In addition to creating a setup that is very surreal, the works are usually

very time-based and mediated.

DS:

I don’t intentionally approach installations though the language

of film. But it’s probably unavoidable as it’s a language I’ve spent so much of

my adult life speaking. My brain has a film bias. To wit – a sinkhole is an

edit in the landscape. A place where there is something, suddenly becomes a

place where there is not. I’m drawn to this as a geographical, material fact

and ominous, psychological tone.

Still from Last Things (2023). Image courtesy of the artist

NN:

This year, the Onion City Experimental Film Festival

will open with your Chicago premiere of Last Things. Your research

collaborator, Suhkdev Sandu, author and Director of the Center for Experimental

Humanities and Associate Professor of English and Social and Cultural Analysis

at New York University, will also attend in person and join the post-screening

discussion. I don’t want to ruin the surprise. But perhaps you could give us a

little sneak peek by speaking a little bit about how this collaboration

started. How did you two meet and what was the research process like for both

of you?

DS:

Sukhdev and I were matched

as part of the UNDO Fellowship, a year-long experiment facilitated by Union

Docs (NY) that pairs writers and filmmakers on a thematic topic of their

choosing. We were one of four collaborator-pairs, each pursuing a different

theme. Which in our case was Geologic Listening. Our conversations weren’t

directly in service of the film. They’ve been more film-adjacent; rambling,

unpredictable and wildly generative.

NN:

Last

question is on coping and staying positive. After the end of the world is

talked about (as in Last Things), what are your next steps? What is the

project in progress? How do you stay positive and productive amidst so much

madness going on around the globe?

DS:

Do collective things with

other people. Resist, build, invent. Treat your physical body, this thing that

carries us around, with gratitude and respect. Appreciate the company of

non-human people.

Last Things by Deborah Stratman, presented by Conversations at the Edge in partnership with Onion City Experimental Film Festival, premieres on Thursday, March 30, at 6pm at Gene Siskel Film Center. Due to popular demand, another encore screening is scheduled at 8:30pm.